Comparing Privilege to a Video Game

For a long time, I struggled to understand white privilege. I'm not proud to admit it. I made the usual arguments: My life has been difficult; I've worked my ass off for everything I've achieved; I've given up time with family and ignored my friends to be successful; I've suffered significant pain and loss in life but focused and pushed forward and earned all the rewards I've attained. How can you tell me I've had it easy?

Obviously, I didn't get it.

I suspect most people who disregard the idea of privilege (or white male privilege to be more specific) often feel the way I felt. This isn't news. There are scholarly articles that cover the topic with real data and better examples. This is simply my personal story.

I never intended to ignore or dismiss the plight of people who had been discriminated against or systemically oppressed. Inherently I understood that large groups of people continue to face challenges I've never faced. For whatever reason, such knowledge didn't translate into an understanding that, regardless of how many roadblocks I've overcome, my road was always a little less bumpy than others.

Over the years, I've seen several attempts to illustrate the reality of privilege to people who thought as I did. The most powerful explanation, in my opinion, is this video about head starts in a foot race. But last week I found a new analogy that hits home for several reasons.

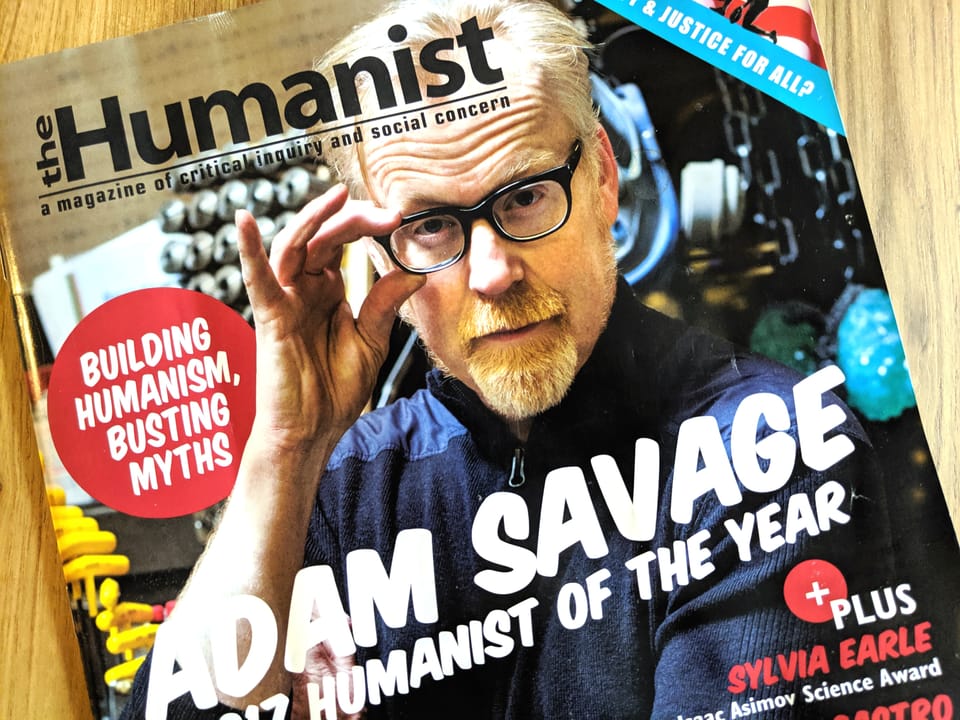

The July 2017 issue of Humanism magazine has been sitting on my desk since, well, July 2017. Adam Savage, Maker Extraordinaire and former Mythbuster, adorns the cover as winner of the 2017 Humanist of the Year Award, and I very much wanted to read the article, even if it constantly slipped out of my todo list.

In his acceptance speech, Adam addresses privilege in a way that calls out my earlier denials and makes absolute sense to my nerdy sensibilities.

When confronted with ideas of privilege, many in the privileged categories feel defensive and look at the myriad, crushing difficulties of their own lives -- financial, emotional, familial. And they conclude that privilege is ephemera, a false construct. My friend, the wonderful science fiction writer John Scalzi, puts it this way: privilege doesn't mean you get a free pass, but in the video game of life you get to play with all the settings on easy. This means you can still lose. And you will suffer because this is the first noble truth of Buddha: we will all suffer. Nobody escapes, but truly, nobody suffers like the poor and the really marginalized communities.

I haven't read John Scalzi's work, even though I apparently follow him on Twitter. But let's give him credit for the idea since Adam does, and let me make a public promise to read his work. But back to the point...

As a boy, my cousins owned Atari and Commodore systems. I loved playing, but the consoles were expensive. My parents didn't have money to spend on video games. They were married young. My dad worked full time and put himself through college at night while my mom stayed home with three young kids. When us kids were older, my mom put herself through college and started a career to help pay for her kids' education. Eventually, they bought us a Nintendo, but all the years of hard work and penny pinching and exhaustion don't change the fact that they, too, were privileged.

Privilege has nothing to do with work ethic. It has nothing to do with blue collar or white collar. It has nothing to do with what you can afford or can't afford.

It's about having a head start, or having a less steep hill to climb, however minimal the difference may be in any particular situation, not because of anything you've done but simply because of circumstance. My parents worked their asses off to improve their own lives and their kids lives. I've done the same. But each step of the way, we faced slightly fewer obstacles than others. No one ever discriminated against us because of our skin color. Perhaps my mom faced challenges as a woman, but neither my dad nor I faced the same. As a single parent, I've had to make choices between work and children. I've felt guilt and pressure at times from the people with whom I worked, so I've seen hints of how discrimination can be applied. Even then, however, my circumstances were of my own making, borne of my own decisions instead of the accidental happenstance of birth.

So I'm now fond of this idea that privilege is like playing a video game. You can still lose. Your character can still die. The game might still be challenging. But many of us are not playing on the hardest possible setting. To me, it's a perfect analogy.

But this begs another question. Life is obviously not a video game, and I fear that comparing privilege to a video game can send the wrong message. People face the brutal reality of discrimination every day, and their lives are profoundly impacted by it. Isn't having the option to reflect philosophically on privilege by comparing it to a video game a result of privilege? Probably. And that's not my intent. I seek merely to understand, and to learn, and to maybe serve as an ally by conveying to others who think as I once did that they're missing the point.

The game of life is difficult enough with the settings on easy. No one should be forced to bump those settings higher unless they choose to. And no one should be allowed to change anyone else's settings without consent.